When I was growing up, I planned to be a writer. I would say that I dreamed of being a writer, but that's not entirely accurate. I did dream of it, but not in the fantastical way I dreamed of owning a horse farm or of living in a straw bale house off the grid with a homeschooled brood of offspring. Instead, I planned for it. I would become a writer. I remember a very particular moment of clarity, in my parents' house, in the bathroom (where as a self-absorbed teenager I spent many an hour gazing into the mirror), when I declared to myself that this was what I would do: I would write books.

I aimed myself at the goal with relative consistency after graduating from high school, though I floundered around a bit, seeking the right degree (theatre? music? playwriting? history?), and it took me until I was 19 (almost 20) to declare a major and work away at it like a person possessed: English literature, of course. At night, I would compose poems on my pre-Windows laptop, eyes closed, drumming out the day's events through my fingertips and transforming the swerving emotions and experiences into imagery, metaphor, allusion, relishing the splendor of language.

I am often asked for advice on how to become a writer. Write, is what I say. And read. Write because you love to. Write what you love. Write as often as you can, doesn't matter what: dream journal, cooking blog, poetry scribbled in the margins. And read read read for the love of it, too.

Reading for a degree in English literature can kind of kill the love, for a few time-crunched years, pencil clutched to underline key sentences and scribble down themes for future essays and exams. Nevertheless, reading widely, reading work you wouldn't otherwise be exposed to, can only be a good thing in a cumulative way. I finished the degree, applied for grants, and went happily off, like a heat-seeking missile, to do graduate work, also in English literature. I was thinking I would do a doctorate and secure myself a job. But things were looking pretty grim for doctoral candidates in English literature back then, and I swiftly grasped that there was only one valid reason to go on in my studies: if I really loved it, then yes, I should. Otherwise, it was time to thank academia for my two excellent degrees, and figure out how to become that writer I'd planned to be.

Skip ahead. Skip over the boring bits, the hours and days and months and years spent writing and reading, and, of course, believing. At the age of 29, my first book was published. It took another eight years to write a second book worth publishing. By that point, I'd lived out the reality of being a writer. I'd been home with young children for years. I'd found paid work here and there as a freelancer and "mommy blogger," which afforded me babysitting, which afforded me writing time.

I kept circling around the question: do I want to be a writer?

Wrong question, as it turns out; misleading, distracting. I already knew the answer: yes, I wanted to be a writer, and had proven that I could be. The real dilemma, the one much harder to face, and more personally painful to articulate, was whether I wanted to continue being a practicing writer if I couldn't make a living at it. And the answer to that, I began to recognize, was no.

Last fall, I decided to switch career paths. I applied to midwifery school. (I also worked frantically on a new novel, feeling the urgency of time ticking down.) This wasn't a decision taken quickly or lightly. I knew what it would mean: I wouldn't be writing books, at least for the length of the degree, possibly longer. A book is the product of time and space and does not simply appear in a burst of inspiration; it's a long-term gamble, is what it is. That's what being a writer is, too. And my appetite for gambling was waning. This does not seem strange to me. The timing seemed ripe for a change. My youngest would be going to school full-time. I'd put my eggs in one basket for two decades, practicing a particular craft, gaining experience and technical skill, and earning praise from peers, without ever making a living at it. In most professions, this would be a bizarre and depressing outcome: imagine a doctor with two decades of training being unable to earn a living. It would be a sign of personal failure; this would have to be an exceptionally bad doctor. But in the arts, it's practically expected, and we all understand that, even if we don't speak openly about it. It's the price of admission. You get to be a writer, but it's for love, not money.

I love writing. But I wanted to support my family. I wanted to give us some stability, to take the pressure off my husband as sole provider, and, yes, to experience the reward of working in exchange for a paycheque. It was time to a get a job-job (or, more precisely, to train for a new career). I was excited and I was ready for a change -- eager, even.

And then the novel I'd been working on sold here in Canada. This happened literally on the very same day I received my acceptance letter from midwifery school. I was kind of a mess.

It felt like the intersection of two possible lives. In one, I was a writer, still doing work that would seem relatively unstable to anyone with a job-job, but many steps closer to earning a living. In this version, I would be building on the foundation I'd worked so hard to lay. In the other possible life, I was starting from scratch, a student in the process of becoming a midwife, also a long-held dream. The decision was agonizing. It took weeks of "discernment" (read: long circular conversations with friends and family; thanks, friends and family), and I questioned myself repeatedly after turning down my place in the program. But there was fresh work to be done. I rolled up my sleeves and revised my new novel. I prepared for my first teaching job.

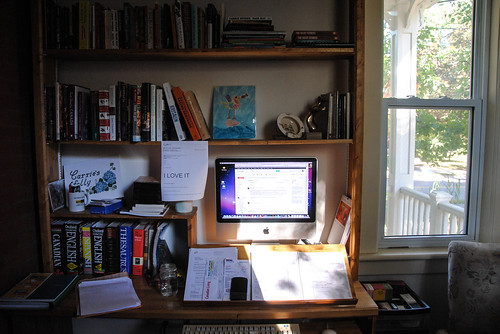

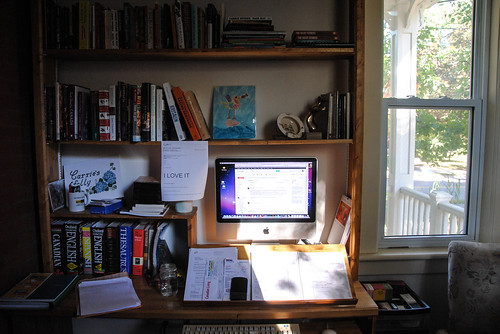

Summer trundled by. I loved sitting my office and working all day. It felt right, as it always has. It feels right.

At last year's Wild Writer's Festival, I was on a panel that included Alison Pick, and she was talking about her decision to work as a writer. She recalled that she'd just been hired at a job-job when her first book sold, so she was able to turn down the job-job and keep writing, and she's never looked back. Every time she'd start thinking, uh oh, I'm going to need a job-job, something new would come along.

As far I'm concerned, that's living the dream. Keeping at bay that wolf at the door.

So I'm publicly updating the plan I had as a teenager staring at herself in the mirror. Seems about time. What I'm planning seems no more unlikely, delusional, or ambitious than the original dream, which was, I'll be the first to admit, highly unlikely, delusional, and ambitious. So here goes. Dare I say it out loud? I want to be a writer whose living is sustained by her writing. I want to be a writer who keeps getting to sit in her office and write, day in, day out, day in, day out. Oh, the places I'll go in my mind.Labels: books, career, midwifery, money, publishing, school, teaching, The Girl Runner, work, writing